By Arlene Bridges Samuels

Celebrating the reality of our Lord Jesus Christ’s resurrection is more important than ever! In the face of all the evil, brokenness, and despair we see throughout our world, we need to be reminded that good triumphs over evil, that truth conquers all lies, and that life overcomes death. Our world is at a critical crossroads, and we need to see the same power that raised Jesus from the dead at work in our world today.

The murderous onslaught against Israel on October 7, 2023, reminds us that truth is turned upside down with a shocking barrage of lies against Israel, Jesus’ earthly homeland. The just war that Israel is battling on the ground is accompanied by a larger spiritual battle in which Satan is continuing his centuries-old plot to wipe out the Jewish people. Why? Because God has always intended the Jewish people to be at the center of His redemptive plans and purposes.

For those of us who are non-Jewish believers, we believe that God graciously grafted us into the unbreakable eternal promises He bequeathed to the Jews. He sustains us as branches on the deeply rooted olive tree. However, among too many Christians and in our churches, Christianity has become all about us, the Gentiles. The non-Jews.

We too often forget our grafted-in Jewish roots. Without God’s establishment of the Jewish people, culture, and identity through Abraham—and His inspired words through Jewish scribes and prophets—Christianity would not exist. God the Father’s rescue plan was embedded in the Old Testament and completed in the New Testament. On Resurrection Day, our Savior, crucified as an earthly Jew outside Jerusalem and gloriously resurrected, returned to heaven in His ascension 40 days later as our High Priest.

Ignoring God’s imperishable gifts through the Jews and overlooking their homeland Israel is a cause for concern. Too many Christians seem unwilling, ignorant, or too easily accepting of terrorists’ lies and fabricated statistics about the Israeli Defense Forces’ battle against Hamas, Hezbollah, and the Islamic Republic of Iran. A refresher in the truths of the Bible is timely on Resurrection Day 2024. We rejoice in the historic and sacred Scriptures in the Bible’s 66 books declaring that Israel, the ancestral homeland, and the land God calls His own, is eternal.

Israel is our spiritual homeland, and Christians are called to do no less than pray for the peace of Jerusalem, the ancient and modern capital. We stand beside Israel not only to receive the blessing in Genesis 12:3—“I will bless those who bless you”—but also because we firmly believe that when we support Israel and the Jewish people, we are taking part in the redemptive story that God is still telling through His chosen people.

During Holy Week, revisiting the four Gospels, the book of Acts, and beyond helps us understand the importance of our Jewish foundation, which sadly crumbled a few centuries later into a Gentile-only faith. Let us recall that Pentecost (Shavuot) is the day the Holy Spirit came upon 3,000 gathered who became Jewish believers. The Gospel swept from Jew to Jew afterwards. For some 10 years after Jesus’ resurrection and ascension, only Jews, with a few exceptions, wore the mantle of our faith and carried the Good News to other lands. Later, God spoke to the brilliant scholar Saul on the Damascus Road. Newly named Paul, he prized his Jewish heritage while preaching and writing the Good News directly to Gentiles in his travels.

Some Bible translations describe Jesus’ own three-year ministry referring to churches, rather than synagogues. He trained His Jewish disciples outdoors, in homes, and on the Temple Mount in the courtyards of the Second Temple. He and His disciples only read from Old Testament scrolls. Jesus was a Jew, not a Christian. The New Testament was yet to be written.

During each Holy week, we still hear misguided pastors and churches teach that “the Jews rejected and killed Jesus!” They fail to understand the events recorded in the Gospels, which indicate Jesus’ popularity and favor with the Jewish people. They fail to understand that it was not the Jewish people at large who killed Jesus; rather, it was an elite group of Chief Priests and their scribes who collaborated with Rome to eliminate Jesus, because they wanted to maintain their power, corruption, and wealth. This is why they had to arrest Jesus in secret under the cloak of darkness, because they feared the people and what would happen if they arrested Him out in the open (Luke 22:2-6).

There were many to blame for killing Jesus: Chief Priests, their scribes, Judas, Pilate, and the Roman soldiers who carried out the execution. However, we dare not overlook the words of Jesus in John 10:17-18: “The reason My Father loves Me is that I lay down my life—only to take it up again. No one takes it from Me, but I lay it down of My own accord. I have the authority to lay it down and authority to take it up again. This command I received from My Father.”

We must emblazon His words, “No one takes it [My life] from Me” into our minds. Jesus willingly underwent suffering and death on the cross to redeem us. Jesus paid our debt of sin as only He could, the Perfect Lamb. God’s redemptive plan offers us new life, new hope, and our eternal homeland! No one could have stopped God’s plan!

The human heart sank into the weakness of human nature by blaming the entire Jewish race for the worst murder in history. In a sense, Christians themselves have forgotten God’s redemptive plan to save us from ourselves by sending His only begotten Son to die as our perfect substitute. The treasure of the Jewish origins of Christianity was camouflaged by placing blame only on the Jews—instead of looking at ourselves or the crucifixion’s accomplices.

Previously, anti-Semitism marched through the centuries with boots, bombs, tanks, and terror in multiple contexts. While German propaganda ruled during World War II, since October 7, 2023, the barbaric Hamas/Hezbollah/Houthi/Iran war turned on a global switch. Aided by toxic world media’s instant, biased news, anti-Semitism’s resurgence moved to deeper depths, darkening human minds worldwide to believe lies and distortions. It has penetrated organizations, universities, institutions, governments, and yes, even churches. Now, here we are five months into unmitigated Jew hatred that is surging throughout the world.

Nevertheless, God’s sovereignty towers far above evil—and wins! In word and deed, we must press in to remain active on behalf of Israel and celebrate our Savior’s world-changing resurrection. May we worship Jesus, our Jewish rabbi under His Prayer Shawl (Tallit).

Under Your Tallit, I dwell safe and secure. Under Your Tallit, my hiding place is sure. Though life is full of struggle, Your joy is fuller still. Under Your Tallit, I’m in Your sovereign will. Jesus (Yeshua) my High Priest, You tore the veil in two. I stepped inside, You welcomed me to share this place with You, both Gentile and Jew. Yeshua, You are the One Who reigns in majesty. Into Your royal priesthood You have adopted me so that I can be…under Your Tallit! (© 1999 Arlene Bridges Samuels)

Our CBN Israel team wishes you an inspiring Resurrection Sunday overflowing with hope! Join us in praises and prayers!

“Praise be to the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ! In His great mercy He has given us new birth into a living hope through the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead, and into an inheritance that can never perish, spoil or fade. This inheritance is kept in heaven for you, who through faith are shielded by God’s power until the coming of the salvation that is ready to be revealed in the last time.” (1 Peter 1:3-5)

Prayer Points

- Pray for strengthened faith and maturity for Christians worldwide.

- Pray for God’s mercy upon persecuted Christians facing torture and death.

- Pray for hope in a chaotic world—trusting God, the Alpha and Omega.

- Pray for Easter safety in Israel for Jewish, Arab, and Gentile believers.

- Pray for wisdom, unity, and victory for Israel’s government and military.

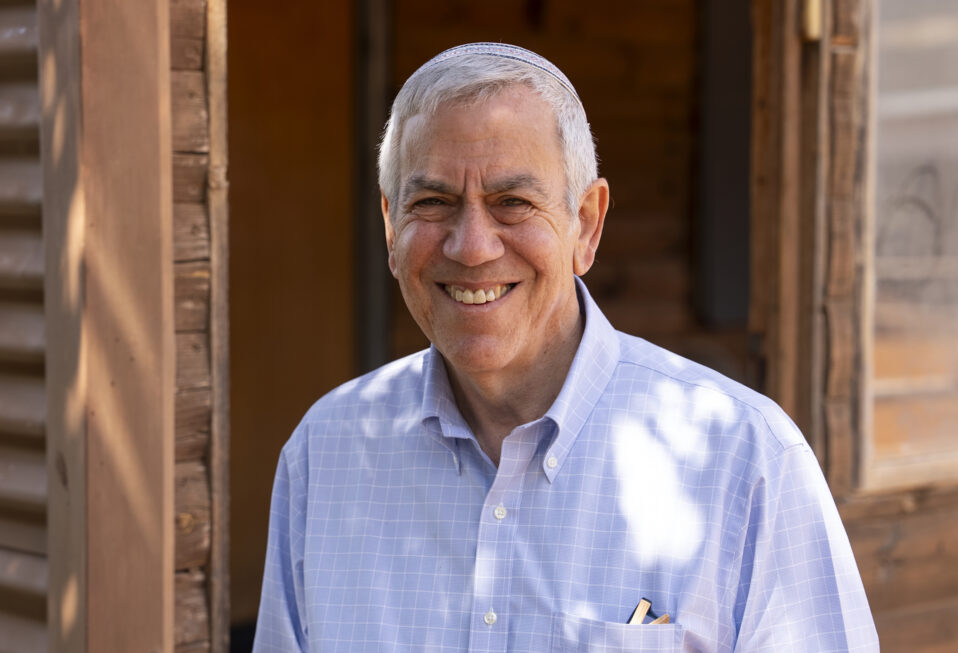

Arlene Bridges Samuels pioneered Christian outreach for the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC). After she served nine years on AIPAC’s staff, International Christian Embassy Jerusalem USA engaged her as Outreach Director part-time for their project, American Christian Leaders for Israel. Arlene is an author at The Blogs-Times of Israel and has traveled to Israel since 1990. She co-edited The Auschwitz Album Revisited and is on the board of Violins of Hope South Carolina. By invitation, Arlene attends Israel’s Government Press Office Christian Media Summits. She also hosts her devotionals, The Eclectic Evangelical, on her website at ArleneBridgesSamuels.com.