By Arlene Bridges Samuels

During Israel’s 2020 Memorial Day observance, Dvora Waysman, an Israeli author and syndicated journalist, observed, “Israel is a country where so many parents have been called upon to bury their children, and the earth is saturated with tears. In the whole land, there is barely a family that has not been affected in the past 72 years, which has not lost a husband, a father or a brother, or a cousin or sweetheart.”

Memorial Day, called Yom Hazikaron, is Israel’s official remembrance of the nearly 24,000 soldiers who were killed during the struggle leading to the establishment of the modern Jewish state or who have since been killed on active duty. In recent years, civilian casualties due to terrorism have been added in the totals. The Defense Ministry’s list reports that since last year’s remembrance, 43 soldiers have died—as did an additional 69 veterans from injuries sustained while serving their country.

Thus, sirens sounded once more in Israel this past Tuesday evening and then again on Wednesday morning. Nationwide, Israelis stood still or stopped their cars to honor family and friends who died defending their small nation in wars and relentless terror attacks.

Israel Defense Forces (IDF)—ground, naval, and air—are composed of citizens from all walks of life, be they Jews, Arabs, Christians, or Druze. Families and friends visit thousands of memorials and graves in the small nation. Gravestones show ages of the fallen—both men and women—at 18 and up, since military service is mandatory right out of high school for both men and women. Men serve for three years and women for two.

Israelis also mark Yom Hazikaron with lowered flags, religious and civil ceremonies, prayers at the Western Wall, and candle-lighting. Our own American military and law enforcement families and friends also grieve loved ones who sacrificed for freedoms. But Israelis have an added reality. The wars and terror are experienced in some form by every citizen, up close and personal. Their country—the Middle East’s only democracy—is in a perilous neighborhood. The hatred for the Jewish nation results in attacks on Israel’s homeland from terror enemies located on their borders with Gaza, Lebanon, and Syria, as well as Iranian forces now actively operating in Syria.

It may be puzzling for many to grasp why Israelis have placed their Memorial Day the day before their Independence Day. It strikes me as a picture of the way life really is. The Jewish Scriptures describe this in Psalm 30:5: “Weeping may endure for a night, but joy comes in the morning.”

Israel’s national anthem, HaTikvah (“The Hope”), helps enlighten our understanding, too. In 1878, Jewish poet Naphtali Herz Imber from Galicia (now Ukraine) wrote the lyrics. The melody was composed in 1888 by Samuel Cohen, who based it on a Romanian and Moldovan folk tune. Just as the U.S. national anthem is embedded deeply into our culture and consciousness, HaTikvah is deeply embedded in Israel’s.

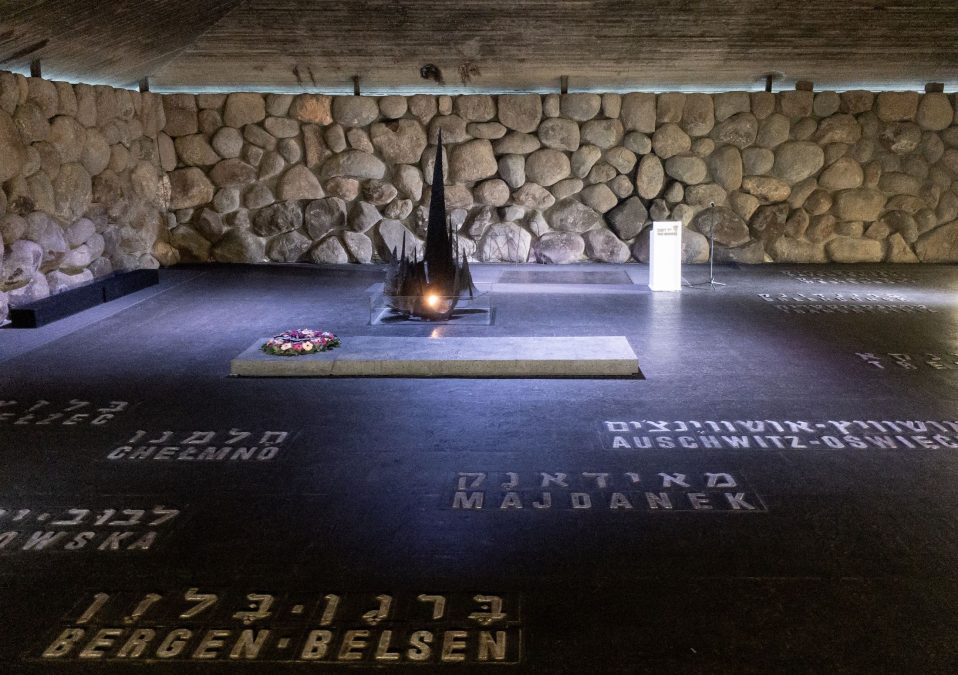

Holocaust survivors sang it in Bergen-Belsen on their first Sabbath after the concentration camp was liberated. Last year, when Israel was in lockdown due to the coronavirus pandemic, the Defense Ministry’s Department of Family Commemoration and Legacy invited Israelis to, “Go out to your balconies, stand by your windows, and we’ll all sing the national anthem together as one.”

The lyrics are stirring and full of promise:

“As long as within our hearts

The Jewish soul sings,

As long as forward to the East

To Zion, looks the eye –

Our hope is not yet lost,

It is two thousand years old,

To be a free people in our land

The land of Zion and Jerusalem.”

During the Diaspora (scattering) throughout the world, the Jewish community prayed for Jerusalem, even in the worst circumstances, holding on to the hope of living there someday. Two thousand years of prayers and hopes were fulfilled on May 14, 1948, when the modern Jewish state was born. Hopes, tribulations, and persecutions turned into joy.

That Jewish sorrow/joy continuum is evident even in wedding celebrations. Couples marry under a wedding canopy (huppah). At the end of the ceremony, the groom steps on a glass to shatter it. The custom signifies joy and sorrow in a national anguish for the beautiful building—then destruction—of the Second Temple. The Jewish people clearly understand the paradox and the realities of mourning, then celebrating. Drawing life out of death.

After the official day of mourning, Israel’s Independence Day—Yom Ha’Atzmaut—takes off into a stratosphere of joy. The celebration marks the end of the British Mandate for Palestine. Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, once stated: “In Israel, in order to be a realist you must believe in miracles.”

When Ben-Gurion read the Declaration of Independence in Tel Aviv, he announced the name of the modern Jewish nation, calling it “Israel”—no longer “Palestine.” Hours later, at midnight, five Arab armies thrust war upon the fledgling Jewish nation. Aish.com, “the leading Jewish content website,” recently ran an article by Rabbi Ephraim Shore that includes these brief statistics about the war’s beginning, as related in A.J. Barker’s Arab-Israeli Wars:

“In less than two weeks the government created the Israel Defense Forces, merging the Haganah (the main Jewish military organization since 1920), Irgun, and Lehi. Israel had 32,000 soldiers but only one third of them had light arms, and no heavy weapons existed. Half had zero military training. Invading Arab armies boasted 270 tanks, 150 field guns, and 300 aircraft.”

Despite overwhelming military might and numbers, the war ended on January 7, 1949, with an Israeli victory. Miracles unfolded in waves that only the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob could have engineered.

The last 73 years of the modern Jewish state have proven the truth of Ben-Gurion’s statement. After the staggering shock of losing one-third of the global Jewish community under the Nazis, almost 7 million Jewish citizens now live in the only Jewish nation on earth. Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics breaks it down: In Israel, the total population is 9.3 million; 73.9 percent are Jewish, 21.1 percent are Arab, and 5 percent are defined as “other,” which includes Christians and Druze.

Israelis will celebrate Yom Ha’Atzmaut much as Americans do, with family, friends, barbecues, dancing, music, and concerts. I have been in Israel on those two days when deep sorrows spilled over into the atmosphere but were then overtaken with celebrations full of fantastic Israeli food and the glittering light of fireworks. The intensity of both was evident.

Praying for the peace of Jerusalem conveyed in Psalm 122:6-8 is a daily prayer for many Christians: “Pray for peace in Jerusalem. May all who love this city prosper. O Jerusalem, may there be peace within your walls and prosperity in your palaces. For the sake of my family and friends, I will say, ‘May you have peace.’” Family and friends are mentioned in verse 8. Let us focus on praying for Jewish families who live with grief daily. Let us also pray for the remarkable Israelis, their vast accomplishments, their will to live, their culture of life, and their continual longing for peace.

Join CBN Israel this week in prayer as the people of Israel observe their national Memorial and Independence Days:

- Pray with thanksgiving that the Lord has miraculously protected and preserved Israel against all odds over these past 73 years.

- Pray that Israelis will come to know that millions of Christians stand with them, both in their deep sorrow over their losses and their joyous celebration of Israel’s independence.

- Pray for each branch of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), that they will have the strength and resilience necessary to protect their country.

- Pray for a strong and stable coalition to form in Israeli politics so that the nation does not face a fifth election.

- Pray that God would continue to use the people and nation of Israel to be a light to all nations of the earth.

Our collective prayers for Israel in a sense reenact traditional Jewish prayers held in minyans. Ten adults compose a minyan, the minimum number needed for public prayer or to hold services at a synagogue. But ours is a worldwide minyan with intercession across every time zone. It is reasonable to assume that someone or some group is praying somewhere in the world for Israel and the Jewish people 24/7. Our prayers can take place in a group, at church, at home, or even while looking up at the stars reflecting on the promises God made to Abraham:

“And I will make your descendants multiply as the stars of heaven; I will give to your descendants all these lands; and in your seed all the nations of the earth shall be blessed” (Genesis 26:4).

Arlene Bridges Samuels pioneered Christian outreach for the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC). After she served nine years on AIPAC’s staff, International Christian Embassy Jerusalem USA engaged her as Outreach Director part-time for their project, American Christian Leaders for Israel. Arlene is now an author at The Blogs-Times of Israel and has traveled to Israel 25 times. She co-edited The Auschwitz Album Revisited by Artist Pat Mercer Hutchens and sits on the board of Violins of Hope South Carolina. Arlene has attended Israel’s Government Press Office Christian Media Summit three times and hosts her devotionals, The Eclectic Evangelical, on her website at ArleneBridgesSamuels.com.