By Arlene Bridges Samuels

The candles are extinguished for Hanukkah 2021, the Jewish Festival of Lights, and are now replaced in many homes with the lights of glowing Christmas trees and festive decorations. Our Christian nativity scenes are on prominent display, with Mary, Joseph, and baby Jesus in a manger. Often lost, however, is the humble yet splendid context of Jesus’ birth in Bethlehem, the birthplace of King David.

Let us take a look at a significant side note of facts and details before we take an imaginative journey to the ancient town of Bethlehem where our Jewish Savior was born. After Jesus’ resurrection and ascension, His disciples and the Apostle Paul traveled throughout the vast Roman Empire to spread the Good News throughout the known world. Tragically, generations later, Gentile believers gradually began distancing themselves from the Jewish roots of their faith and Jesus’ Jewish ancestry. As a result, centuries of Christians found themselves vastly disconnected from the origins of their faith.

Yet, over the last few decades, Christians have made monumental strides toward rediscovering the Jewish roots of our faith. Part of the heightened awareness of Jesus’ ancient Jewish culture and setting is the fascinating connection between Migdal Eder (Tower of the Flock), the shepherds in the Bethlehem fields, and the shepherd boy who would one day be crowned King David. This glistening thread of history is as wondrous as the star that later guided the wise men to the child, Jesus, who would grow up to become the “Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world!” (John 1:29).

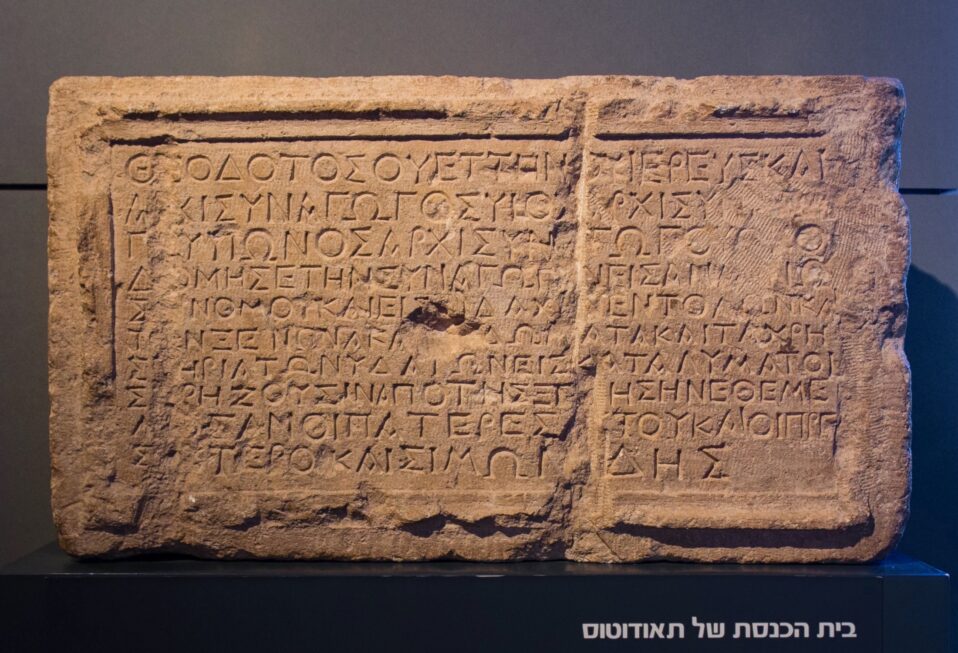

The Tower of the Flock no longer stands, but Scripture reinforces the shepherds retelling their stories for hundreds of years until a Byzantine monastery was built over the site of Migdal Eder in the fourth century. The Bible mentions Migdal Eder (or Edar) in two specific passages, Genesis 35:21 and Micah 4:8. The Hebrew word Migdal means “tower” and Eder means “flock.” This important tower stood on the road between Bethlehem and Jerusalem, which are approximately six miles apart.

In Genesis, Jacob cast his tent at Migdal where he buried Rachel, the love of his life, who died giving birth to Benjamin. Then Micah 4:8—a prophecy written around 700 years before Jesus’ birth—reads, “And you, O tower of the flock, the stronghold of the daughter of Zion, to you shall it come, even the former dominion shall come, the kingdom of the daughter of Jerusalem.”

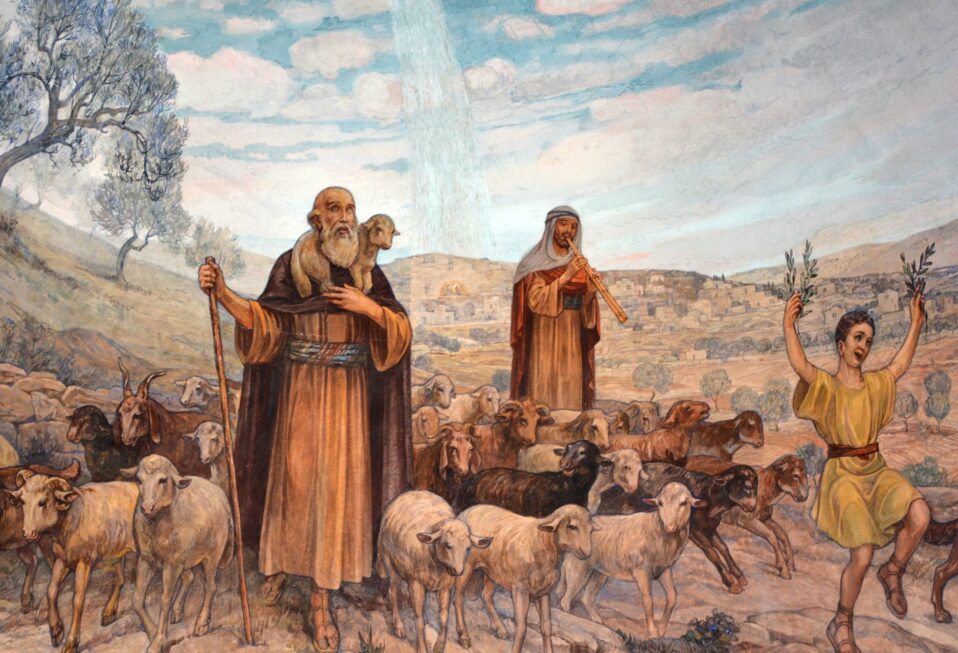

As we know, shepherds and sheep occupy a prominent place throughout the Bible. They are mentioned 500 times! The beloved Psalm 23, written by the shepherd king, David, enshrines our Lord as our Shepherd along with Jesus’ own words. In John 10:11 Jesus declared, “I am the good shepherd. The good shepherd gives His life for the sheep.” He then says, “As the Father knows Me, even so I know the Father; and I lay down My life for the sheep” (John 10:15).

King David was born in the town of Bethlehem, which is known along with Jerusalem as the City of David. Since the mention of Migdal Eder appears in Genesis, David would have known about Migdal Eder from Scripture and from shepherding. There in Bethlehem, the prophet Samuel anointed him to be Israel’s king (1 Samuel 16:1-13). Jesus’ earthly adoptive father Joseph was of the lineage of King David, a fact that is intentionally established in the first chapter of Matthew’s Gospel.

Joseph and Mary traveled from Nazareth to Bethlehem to register for the obligatory Roman census and pay taxes. By imperial decree, everyone was required to go to their ancestral town. Surely it was no accident or coincidence that the young Jewish couple would return to Joseph’s hometown at this specific moment in time. Rather, it was all part of God’s plan that Mary would give birth to Jesus in Bethlehem—in close proximity to The Tower of the Flock.

For centuries, shepherds were completely familiar with The Tower of the Flock. The tower and the Bethlehem fields were their workplace. The stone structure was two floors high, allowing the Chief Shepherd to look out over the flock for predators from the second floor. The shepherds also led the ewes from the fields into the tower to give birth.

The late Dr. Jimmy DeYoung Sr., in his Day of Discovery program, described his research on the shepherds’ skill: “They would reach into the mother’s womb and pull out this newborn lamb. Then they would reach back and get some swaddling and snugly wrapped the lamb because if it harmed its limbs in any way, it would be disqualified as a [Temple] sacrifice. Once the lamb was wrapped, they would lay it in a manger until it calmed down then they would unwrap the swaddling and let it run off to its mother for some food.”

When angels appeared to the shepherds in the Bethlehem fields with their glorious birth announcement, the shepherds appeared to know where to go based on the directions provided to them in Luke 2:11-12: “For there is born to you this day in the city of David a Savior, who is Christ the Lord. And this will be the sign to you: You will find a Babe wrapped in swaddling cloths, lying in a manger.” The connection between the birthplace of Jesus and the location of The Tower of the Flock, where the Temple lambs were born, is fascinating to say the least.

The Jewish leaders in charge of Temple sacrifices chose the shepherds since they were experts in animal husbandry. They appointed them as Levitical priests. The lambs they tended on the birthing floor of Migdal Eder each year were special. When the lambs reached a year old, the shepherds herded thousands of them to Jerusalem for Passover—what ancient Jews called the Day of Lambs—to present them to the Temple priests. The priests inspected them, then chose the ones without spot or blemish as the sacrificial Passover lambs. It is a description of our Savior, Jesus, the Perfect Lamb of God, also sacrificed at Passover for us.

Allow this realization to sink deeply into your heart. These particular events—Jesus’ birth, life, and death—intricately link with the ancient Levitical shepherds and the Temple-destined lambs. When Jesus identified Himself as the Lamb of God, He chose a metaphor and image that only His Jewish audience could fully appreciate. Then, a few days later, the dramatic events of Jesus’ final Passover, subsequent arrest, trial, and conviction eventually culminated in the Perfect Lamb of God being nailed to a tree with His blood splattered outside the walls of Jerusalem. Simultaneously, the priests in the Temple were slaughtering the Passover lambs.

Throughout the Christmas season, our decorated trees and homes are a wonderful source of joy, tradition, and family memories. Yet may we never forget to reflect upon that first Christmas when Jesus, the Perfect Lamb of God, was born in Bethlehem not too far from where the unblemished sacrificial Temple lambs would have also been born. May we remember the true meaning of Christmas, when Jesus entered time and space to be Immanuel, “God with us.” This Christmas let us also reflect upon these life-changing words about Jesus’ profound and permanent sacrifice for all of us:

“And every priest stands ministering daily and offering repeatedly the same sacrifices, which can never take away sins. But this Man, after He had offered one sacrifice for sins forever, sat down at the right hand of God. … For by one offering He has perfected forever those who are being sanctified” (Hebrews 10:11-12, 14).

Please join CBN Israel in prayer this week as we prepare to celebrate Christmas:

- Pray that the Christian community in Israel and throughout the Middle East would be encouraged in their faith this Advent season.

- Pray that Christians will focus first and foremost on the core message and hope of Christmas—that Jesus is Immanuel, “God with us.”

- Pray that our Christmas celebrations will include blessing others who are in need.

- Pray for CBN Israel as generous partners make it possible to share God’s love and goodwill with impoverished families, elderly widows, lonely refugees, and more.

Arlene Bridges Samuels pioneered Christian outreach for the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC). After she served nine years on AIPAC’s staff, International Christian Embassy Jerusalem USA engaged her as Outreach Director part-time for their project, American Christian Leaders for Israel. Arlene is now an author at The Blogs-Times of Israel and has traveled to Israel 25 times. She co-edited The Auschwitz Album Revisited by Artist Pat Mercer Hutchens and sits on the board of Violins of Hope South Carolina. Arlene has attended Israel’s Government Press Office Christian Media Summit three times and hosts her devotionals, The Eclectic Evangelical, on her website at ArleneBridgesSamuels.com.